The Colors of Siyam

By Jana Amin

Identifies with the nation of Egypt

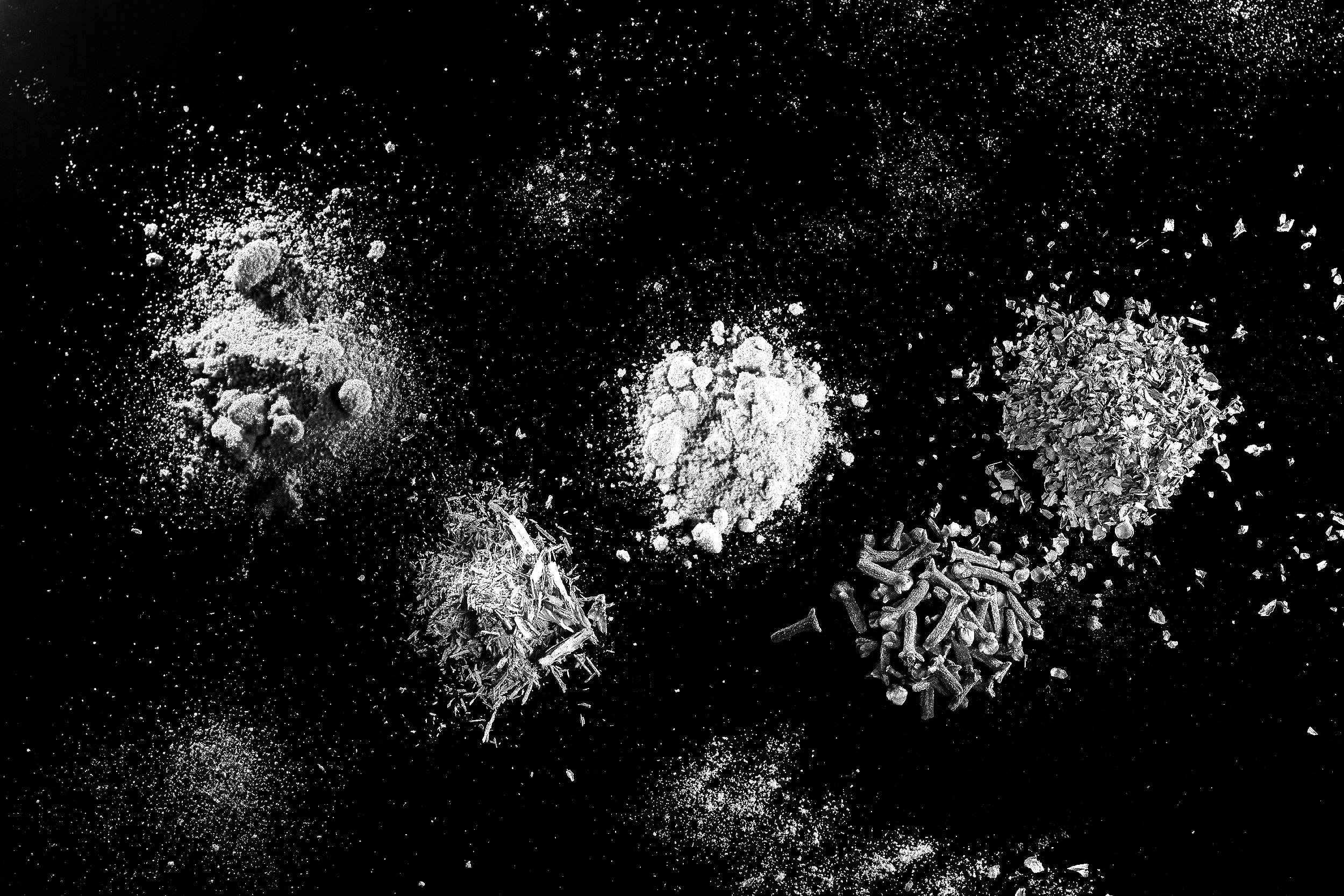

Perched on the balcony of my grandparents’ apartment, I observe as Fatima, the young woman carrying a platter of spices on her head, retreats into an alleyway at the end of the street. As flashes of red paprika and coffee-brown aniseed atop her black hijab blur into the distance, I feel Cairo retreat, too, the honks that otherwise characterize the city subsiding, her chaotic facade replaced by a softer, more vulnerable hum.

I love this transition of hers: when the city’s residents flock inside their homes for maghrib, sunset prayer, to break their siyam (fast), leaving her and me, together, alone.

I too should be going inside, helping my family (or rather, my grandmother, aunts, mother) as they scuttle around the house preparing for iftar–the meal to break our fast. But a day spent fiddling around in the kitchen marks itself all over my body; in the odor of white onions stuck under my nails, the crumbs of sesame that line the folds of my dress, the little burn on my wrist my grandmother has lathered in honey.

My body, exhausted from a day of fasting, clings to the adhan, curling up into each of its echoes, imagining the imam’s words turning from bellowing recitations of the Quran into devastating flashes of color across the sky, at once ferociously pink and orange and gold and purple.

An hour ago, I could feel the inside of my stomach empty, the hollowness amplifying the sound of every grumble that built up within me, the force of hunger eleven hours in at times so striking it forced me to grab the nearest wall, table, anything for stability.

But now that I can eat, now that the sun has dipped beneath the horizon, leaving behind this splatter of color perched high above the city for the few of us watching–and not busy eating–to see, I refuse to get up.

* * * *

Siyam is hunger, yes. But siyam is also control, generosity, hospitality, community. Siyam is the realization that a day spent neither drinking nor eating is, indeed, possible, that yes, I can do without my morning iced chai, that no, my body does not need a 10am maple walnut scone to survive.

Siyam is the lightning bolts of craving that dash through your body, coming and going as they please, reminding you of the Flutes chocolate you have not had in years and the cheese-stuffed kunafa that once bathed you, just a child, in syrup from El Abd’s cafe in Cairo.

Siyam is a reminder of all that is not attainable in this world, all that there is to be grateful for, all that there is to ground oneself in. Siyam evokes those in the world who cannot afford to eat, the hunger they might never overcome, the help we each often should–and fail–to provide.

Siyam is the sensation of a warm, full body, stuffed with family and food and friends just as much as it is the sensation of hollowness, of vulnerability, of isolation.

I am told, growing up, that, above all, Siyam is supposed to be a reminder of Allah. Of the blessings He endows upon each of us–and the trust we must put in Him to get through a day of fasting, to get through the month of Ramadan, to get through an entire life spent serving Him.

How else does the sky go from pink to purple to orange to gold if not by His will?

Even today, my grandmother–the one I will beg to teach me Egyptian recipes once my mother, brother and I move to the quiet Boston suburb of Milton when I am twelve–insists that twenty-year-old me does not remember God enough during Ramadan.

I seldom pray or read and recite Quran, instead spending every Ramadan after our move on a quest to replicate the Cairene transition from chaos to calm in this new country.

But in Milton, the adhan does not sound. My mum cannot cook (she never had the patience for it), so days fasting are spent curled up watching whatsapp videos sent by family in Egypt documenting their iftar. I watch, breathless, as my grandmother’s unsteady videography shows us table spreads overflowing with food and rooms overflowing with people. I rewatch each of her videos so many times I lose count, the fourth replay allowing me to make out large platters of rice sweetened with raisins and toasted nuts, while the fifth gives me a glimpse of my cousins, so much older than the last time I saw them, praying in congregation with the rest of the women in my family.

With each shaky twenty second clip I watch, my body–and heart–aches. In diaspora, my body and heart long for what they cannot seem to find: food, home. Maybe, even, God.

Science teaches me there is something primal about hunger. But I am convinced there is something even more primal and all-consuming about hunger in diaspora.

When my mother, brother and I break fast on the first day of the first Ramadan we spend away from Egypt, I am twelve. All I can hear, too loud, is that Cairene transition at maghrib, transposed onto the still-foreign silence of American suburbia, where I can make out the sound of cars rolling down streets a fifteen minute walk away.

There is no transition to calm in suburban America, my town’s silence perpetually as expansive as its parking lots and backyards. In the background of our house, the hefty speaker I carried 5,421 miles with us blares Egyptian Ramadan music, upbeat Arabic music I have been curating for a week, music my mother insists we don’t need, music that I cannot escape thinking represents something (but what exactly?) that we’ve lost.

My mother calls this the most intimate iftar she’s ever known, and I marvel, angrily, at the way in which she spins everything so seemingly effortlessly, insisting that the way in which she has spun my world is for the better.

An electronic adhan sounds off of her iphone 6. I look outside the window, desperately strip-searching the sky for colors I know I will not find. It turns out, Tim Cook cannot transform sound into color the way the Imam could.

The gray sky overshadows any color there may have been, dulling any hunger I had pre-iftar, pre-move, with it. Can I force myself to feel hungry without His will?

From someone surely as homesick as I, I once read that home could be passed from one body to the next, like a secret whispered in the ear. That first Ramadan, like the Ramadans that have come after it, I could feel my body forgetting its home with each bite I chose not to take, overwhelmed by a hunger I could not–and still cannot–truly describe.

Perhaps paradoxically, however, I love explaining Ramadan to Americans, anticipating the “what? not even water?” that surely follows my monologue, mocking every time one of them asks how come Muslims don’t pass out if they fast for a month (we would, but fasting is observed from sunrise to sunset for a month), laughing when my freckled friends peer into my eyes and look down at my skirt and, incredulously, ask “you’re Muslim?”

I love explaining Ramadan to Americans because I feel a little like God’s chosen child, sent to educate the non-believers about this faith-tradition, as if I am not teetering on non-belief myself, streaks of color in the sky the only thing tying me to Him still.

But, each time my grandmother reprimands me for not praying, each time I am reminded of my hunger for a place I am not sure I can still call home so many years later, each time I am asked to grieve for His people’s losses (of which the Syria, Palestine, Kashmir, Sudan in the world remind me are so many), I see those streaks getting duller and duller.

And I long to grab onto those flashes of Him I once saw, ask Him to rope me up towards Him, instill in me a hunger for Him I long to–but do not always–feel.

* * * *

I gain weight every time I visit family in Egypt, the sounds of my grandmother chasing me around the house in heavy flipflops telling me I have not eaten enough clinging to me for months after my return to the US.

She has me walk to the corner of the street each day for fruits and vegetables she is sure I have missed. And I stand next to her day in and day out as I learn to make recipes I know will otherwise go extinct, no one else in my family bothering to ask her how many spoons of ghee goes into her scalding hot Om Ali or how much water to add to make the perfect katayef, stuffed with white cream-like ishta and sprinkled with salty, roasted crushed pistachios.

I humor her in the kitchen, even as she makes subtle references to my religiosity or talks, eyes brimming with pride, of all the Quranic chapters my cousins have recently memorized. We both know I have not touched a Quran in far too long.

She does not realize it, but all her talk does little to increase my appetite. If I knew how to make myself hunger for Him–for Egypt, for food–I would have let myself starve long ago.

So, one Ramadan, COVID Ramadan, seven years after my family’s move to the US, I consider not fasting. I’d just watched an instagram video of some Imam proclaiming fasting without proper prayer invalidated the fast. And, I felt, in a world drowning in pandemic induced silences before and after iftar, that He was nowhere I could find.

I remember texting my Egyptian-American best friend, quarantined just twenty minutes away, asking him how his Ramadan was, wondering if he would be able to see through the fluorescent lights of our iphone screens how mine was.

But, on paper, mine was no different. I prayed, a couple of times, as I always end up doing. I fasted every day. I cooked whenever I could, going from aspiring diasporic chef to confident (stereotypical even) Egyptian woman in the kitchen in the matter of just a few months.

But I could not shake that instagram video, nor the world’s resounding grief for lives lost from me that Ramadan.

I no longer found it in me to be surprised by my lack of appetite post-iftar. After missing Egypt so much, my hunger for her began to dull, memories I had of packed, vibrant Cairo streets becoming ever muted. The Cairene sunsets I once lusted over drifted away from me.

Near the end of that Ramadan, a little voice in my head began to wonder: did I still know how to be hungry?

* * * *

For my family’s 9th and 10th Ramadan in the United States, for which I am eighteen and nineteen, I start a tradition. We host large iftars, filling up the house, thirty, then forty, then fifty people threatening to unravel our town’s suburban peace with all their unabashed brownness.

I start cooking at 6am, the notes app on my phone perpetually pulled up with a list of dishes I am making, sent to me by my grandmother. I cook and cook and cook, and in the stress of making a red vinegar sauce for the Egyptian carbo-load dish my friends have requested, I tell myself I have little time to think of Allah.

I skid across our kitchen’s dark stained wood floor, dusting our white marble countertops with flour in my wake. Occasionally, I am struck by how much wider and taller the cucumbers are here, by how much less black the eggplants I attempt to make moussaka with are, by how much more effort it has taken me, here, to just find the ingredients that line our pantry, trips to Syrian, Armenian, and Desi grocery stores governing my entire week.

On days I cook maniacally for these iftars, I never feel hungry. Making food feels oddly dissociated from eating it. I cannot, while fasting, taste the food I am making, but I trust (maybe He is somewhere in my kitchen after all?) that it will, by maghrib, be edible, warm, ready to be shared.

When that evening’s fifty Muslims I’ve met through college walk through my Milton front-door, I am thanked, profusely, told, over and over again, by girls my age donning colorful hijabs–my best friends actually–that to cook and feed during Ramadan will bring me blessings.

As I pipe the last dollops of meringue on a lemon tart I decided to make just two hours before maghrib, I overhear a conversation about aya 138 of the Quran, a page out of the Quran’s most widely cited chapters, Surat al Baqarah.

The number–138–sticks with me. Long after the sky has beckoned the Mahmouds and Maryams at my house to the final prayer of the day, I sit in bed and look the verse up. It speaks of immersing oneself entirely in His belief.

The section is coined ‘the color of Allah.’

On my next visit to my grandmother’s apartment in Cairo, I sit outside on that very same balcony around maghrib time, waiting.

Unsurprisingly, Cairo never calms, instead her chaos raging in those transition hours of the evening, as more and more of her inhabitants work up the courage to face her otherwise unbearable heat.

I miss having her to myself. And I long for enough quiet to imagine the Imam’s words as streaks of color again.

In the sky, I look for a sign–any sign—that I should continue to fast. There are none. Maybe I will just have to trust in the colors I cannot see after all.

Jana Amin is an Egyptian-American advocate and community mobilizer for young women in and from the MENA region. She is an author, visionary, and speaker on a mission to uncover what she knows each girl possesses: a vision and a voice. An avid non-fiction writer, Jana has previously been published in the Koukash Review and Azeema magazine, weaving her personal experience, social-impact work, and love of the SWANA region together. For her advocacy, Jana has been recognized by nobel-peace laureate Malala for her work, and was recently named to Arab-America’s 20 Under 20 list. Jana has been featured in over 40 publications, including NowThisNews and MarieClaire Arabia, and her work has received awards from Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and the Chegg foundation.