sêva: the apple blooms through tainted soils

By Dalal Hassane

Identifies with the nations of Syria & Kurdistan

A soaring glow; the headlights are all that illuminate the path ahead. We clap to the beat of the traditional melody that rapidly yet mystically fills the pickup truck. The women of the family we were staying with, whom my mom always said practically raised her during her time in Eastern Kurdistan, sing the songs that have found their home in Halabja for years. Had we not been sitting in the back, I know they would have joined hands as they danced the halparke, a treasured custom in the homeland and diaspora. They would have taken each step with ease, shaking their shoulders in the routine Kurdish fashion.

Fast-paced, poised, they would dance.

But I stop—I stop when I notice everyone glancing to a path that leads to a dark array of houses, nothing too distinct from the simple yet sturdy residences I have come to associate with Halabja. My mother turns to me to explain softly: “That’s where they believe to have found my father.” The rhythmic clapping halts. The music lowers. Halabja feels just a bit darker. Colder.

I notice my mom’s face change, but it is one I recognize. This face I remember from when I was around twelve, when I began to learn of Halabja. Mama’s Halabja.

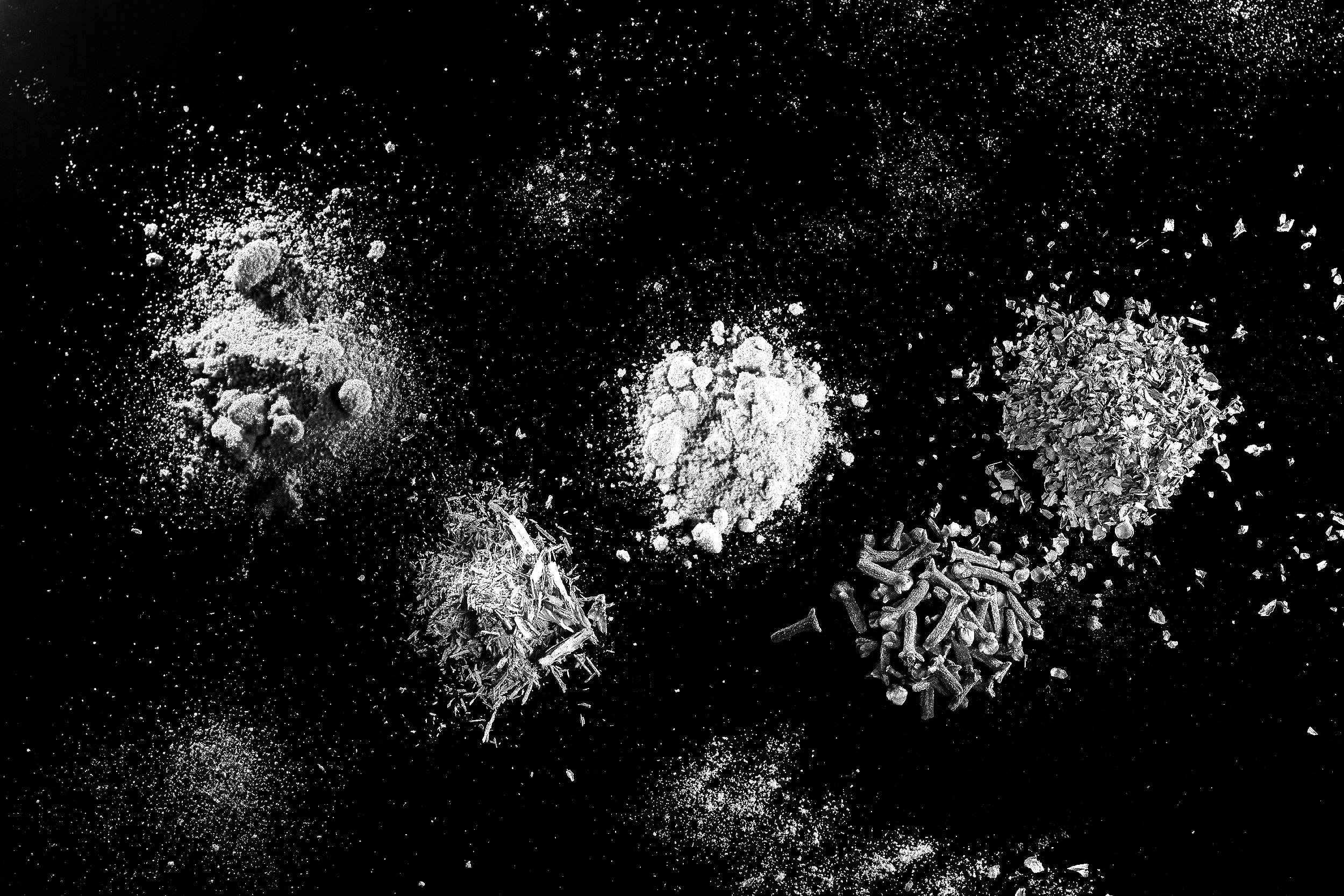

March 16, 1988. Saddam Hussein’s forces gassed the town with cyanide gas—scented strongly with green apple—as part of his genocidal campaign against the Kurds. Over 5,000 martyrs, including my mom’s father and her childhood best friend. This tragic day, one that has been forcefully imprinted into Kurdish history, is what elicits the immediate eyebrow raise from people in Slêmani when we tell them we’re visiting Halabja, the city that people have deemed an emblem of genocide. The tendency to avert one’s eyes to disguise the look of discomfort, of questioning, of exasperation.

It takes a few moments for my mother’s smile to return. For everyone to continue their choral performance. But I look back to the path, long lost in the mountains to the speed of the truck. I wonder what this looked like from the planes; if each path, embedded with memories and histories of joy, was simply lost.

I dwell on how the image of this road over 30 years ago was one that depicted death, and only death. I picture the horrified look on Mama’s 6-year-old face as she realized their city was under attack. That her land, already ripped away from her by occupation, was crumbling to pieces. The smell of apple.

Apple. Sêva.

To attract the children, Mama said. To attract more casualties. Because under occupation, Kurds are no more than bodies to be exterminated. Numbers to boast. Statistics, martyred to the cyanide gas that permeated into Halabja’s deep soils. As Mama told me her stories, I wondered whether she believed herself that Halabja’s fields sprouted nothing more than memories of ruin. But we continue driving through the city’s endless roads. I look out to the vibrant sunflower fields, and though it is dark, they radiate like the roj—sun.

At that moment, my wonder fades.

***

The youngest daughter, Hêvi, in her vibrant red dress, adorns the room with her smile as her aunts ululate with pride. Each of us is wearing jili Kurdi, Kurdish dress. In my head, I am entranced in a game of identifying as many different color dresses as possible. Traditional songs — Kurdish, Arabic, and Farsi — cast a warm shine throughout the room in tunes of resilience.

I cannot recall a time I questioned my own beauty wearing Kurdish clothing. It felt right, like I was meant to don the designs of the homeland as my luminescent gown drapes to the ground. Perhaps it was also the communal nature of the dress. Just a few hours prior, we had been digging through bags and bags of dresses from Hêvi’s older sister, Zoya’s, closet. I could choose from any color imaginable, and nothing made her happier. Nothing made this family happier than providing for those who entered their home, those whom they immediately considered their own.

Yet, just a few days prior, both my mom and I were dreading our stay in the town. Hêvi, the bride-to-be, had invited us to her henna ritual, prompting us to go earlier than planned. Having spent most of the trip in Slêmani, known as Shara Hayataka (The City of Life), we even brainstormed excuses to shorten our time in Halabja. All I had ever known of the town was its ghostly atmosphere, the memories of the past scarred in every village. When Mama shared her stories of growing up in Kurdistan, it was left unsaid that I was meant to associate Halabja with violence. Mama, who always introduces herself as a Slêmani Kurd, attempts to conceal her connection to the land in every way possible. The land that she always says rooted most of her childhood pain.

But as we harmoniously moved our shoulders, taking each other’s hands, I only ever felt joy. I never experienced this land the same way my mom did, and I never will. I grew up hearing about her childhood of displacement, of mourning, of violence. I felt as though I needed to mourn for the life she could have lived. Anytime I felt I could revel in the beauty of my nishtiman—homeland, guilt rushed through me in an internal pulse.

Mama only ever saw and felt a Halabja of sorrow, the Halabja she experienced in her childhood. Maybe this is why it’s difficult for her to view Halabja as anything more than the violence of the past.

Maybe it is why she still smells apple.

As we hugged each other, I felt a sisterhood to these women, some of whom I had only met hours before. Each time I looked to my mom, her smile mirrored Halala’s, the matriarch of the family. Their smiles encapsulated their serene pride as Kurdish women; moreover, their pride as Kurdish mothers.

Though her love for Slêmani is unquestioned, there is not a single time I doubted the genuinity of her laugh in Halabja. She did not have to pretend to like the food, to be engaged in conversation, to happily entertain intrusive questions. She felt natural, she felt at home. She felt cared for and cherished.

So did I.

***

We continue to pass by old buildings and old neighborhoods, which have yet to recover from their time in Ba’athist Iraq. Bullet holes are still deeply pierced into the walls of many of these structures. The Halabja monument, in the shape of a hand, is visible from afar, one of the tallest buildings in the town. From our shorter stay in Halabja just two years prior, I knew the haunting images and figures that were displayed inside the monument. Tanks speeding through the dirt roads. People running, sprinting. Bodies filling the streets.

Still, they clap. They smile. They sing. And I am still struggling to understand why. Why, as we drive through a town that lay thousands of bodies martyred to genocide, do their smiles persist? Why is Halabja a land of happiness to them? They remember Halabja’s past, but they experience it, feel it, in its present being.

Eerily, I picture the smell of apples once more. How it must have been to smell it so distinctly. The moment they realized the fruit’s sweetness was tarnished. That the instant of inhale would be fateful. Suffocation. Exhalation, now a privilege.

***

But Halala and her children show us the town’s beauty. They show us the grand mountains that have held our homeland together for centuries.

هاوڕێمان نیە جگە لە شاخەکان

We have no friends but the mountains.

They still stand, they are monumental. The look of pride in their faces as they show us Halabja’s waterfalls, the sunflower fields, the vast history and traditions; this is Halabja. Their smiles replenish the once poisoned roots that eternally embrace the land. In a land that has seen immense bloodshed, that has been given a direct association with one day, one month, one year, they place it in the present. They hold their heads up high when they say they’re from Halabja. To them, Halabja is joy. Halabja is history and resistance. Halabja is the majestic falls that quench their thirst. It is the ripe pomegranates that are celebrated during the town’s September festival. It is the sounds of Hawrami and Sorani words that transcend the Iraq-Iran border. It is the people. This family. The land.

Mama.

Halala’s hands bleed with mulberry. Her son, Brwa, raises a preserve, a farm, filled with hundreds of plants. Their family’s care extends to the preserve. I see Halala’s caring and selfless nature in Brwa. He does anything and everything to make sure these plants experience the utmost care. That they feel loved, held closely to his heart.

Here, with Halala, in her family’s preserve, I can only ever imagine staying. When I say I have roots in Halabja, I say it with the utmost pride for my ancestral history. Halala’s roots, her family’s creation of roots in this preserve, are what give Halabja its beauty. They place Halabja in the present and make it a place of creation. They acknowledge the pains of the past, but they plant its potential for the future. Saddam tried to reduce Halabja to a place of death, lost to the scent of apple. But it is people like Halala, like her family, who give Halabja life. They plant seeds of resistance and care for the land. They center Halabja in the present moment, uplift it.

They make people like Mama, who have only known grief and fear in this land, proud to be from Halabja. They remind her of care, of community. They remind her of the mulberry trees that ripen each summer, the dances and music that have surpassed generations, and the endless colors of jili Kurdi.

They remind her of what Halabja was, is, and continues to be.

Dalal Hassane is an undergraduate student at Harvard University studying History & Literature and Social Anthropology. She was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois, but is originally Kurdish and Syrian. Dalal is interested in exploring themes of memory, preservation, and resilience in Kurdish and Arab communities, and hopes to use writing as a means of fostering understanding and solidarity. She loves to make handmade jewelry inspired by traditions from her ancestral homelands.